Training is a craft: How to Structure a Session

There's no single "right way" to structure a training session, but there are many wrong ways. A session is only "wrong" if it doesn't help you get the results you're after. Many of today's training sessions are based on tradition, not reason. A major misconception is the unspoken assumption that a training session must last an hour. However, the duration of a session should only be determined by what's needed to signal the appropriate energy pathways or develop a specific skill. The idea that a workout must be an hour long comes from a cultural pressure to rate our work by the hour. This makes it hard for the average person to grasp that you can achieve a lot in just a fraction of that time.

The first lesson is simple: a session should only last as long as it needs to send a signal strong enough to trigger adaptation—no longer, but no less.

Other faulty assumptions come from the dogmatic adoption of scientific research principles. Fitness professionals often emphasize that the average person should use the same protocols as top athletes because many of these have been validated by research. While this sounds correct, the principles can differ drastically depending on the context. For example, in world-class endurance athletes, training at high intensity (above 75% effort) makes up less than 10% of their total training volume. If we applied that same principle to the average person, we wouldn't see a strong enough training effect because their distribution of training volume can be up to 400% different.

The second lesson is that training is individual. We all respond differently and require specific intensity, duration, and movement selection.

By dispelling these "rules" and providing a framework for the "how" and "why" behind a format, we can make planning your own sessions or modifying existing ones much easier. Even more importantly, creating a session and feeling its effects is one of the most rewarding parts of training. Unfortunately, we’ve been pressured to outsource this to "professionals" who more often than not simply copy and paste a list of exercises and rep schemes.

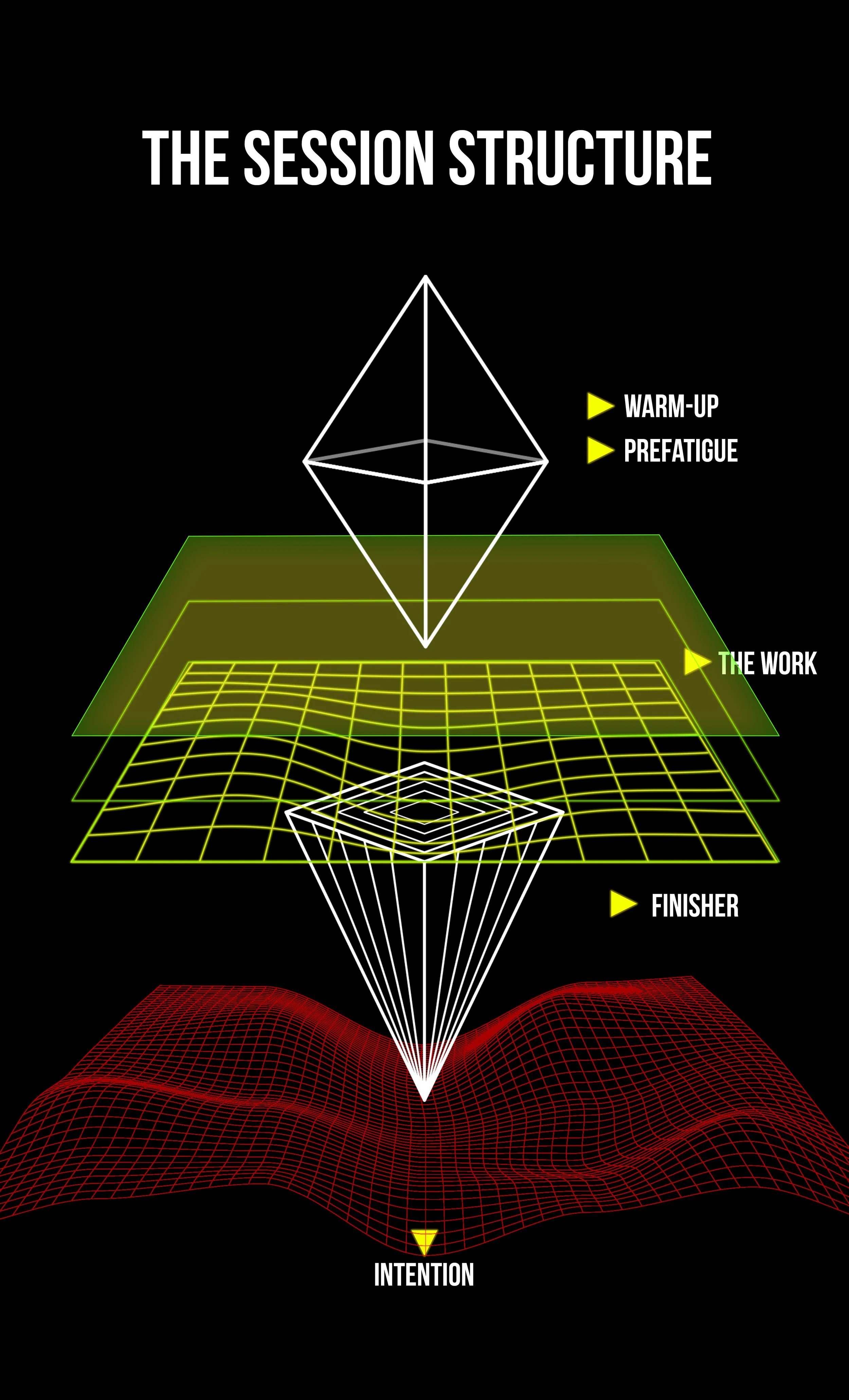

The session structure I'm going to cover is experiential. What I mean by this is that the combination of exercises, reps, sets, time domains, and intention not only enhances physical performance but can also lead to something much more profound and enlightening: insight into our own behavior and state of consciousness.

The Craft of Training

Creating training in this style is a craft, and you must become a craftsman. The Japanese call this "shokunin." While it directly translates to "a person and their occupation," its cultural meaning is much deeper. It signifies a dedication and commitment to the quality of one's work as a moral obligation to society. Shokunin often believe their "soul" is embedded in their work, which gives you a glimpse into their purpose of chasing perfection through iteration.

When we try to conceptualize a style of training that leads to profound personal insight, it's useful to understand this concept because it is more than just exercise. Training is the literal crafting of our behavior. It's the honing of our reaction to hardship and often serves as a reference point for our personality.

Creating a powerful training session is a repetitive and sometimes regressive process. I’ve been writing sessions for myself and others for over 20 years—that’s thousands of sessions I've personally written and performed—and I still don’t get it right every time, and you won’t either. The benefit of learning this style of training design is that you can intentionally set the circumstances for how you want to feel. This goes far beyond the usual "endorphins" or "exercise makes you feel good." It reveals why training can regulate states of consciousness, help determine personality traits, and why it's often more effective at treating depression than pharmaceuticals.

Intention

This is the most crucial part of a session. Just ask one very simple question: "What do I want to get out of this session?"

This is difficult to answer because most people have never thought beyond superficial reasons to train (which are, by the way, perfectly valid reasons to train). Not having a purpose is often why people stop training altogether. In that case, I'd argue it's better to avoid training until you have a reason to.

Your intention doesn’t need to be tied to an objective outcome like, "I need to add 10 pounds to my bench press." It is simply an acknowledgment that you are aiming for something. In some ways it’s better to think about it as “in-tension” — the amount of pull between two points, or where you are and what you want to experience. More often than not, my intention is just to explore and discover new sensations or my relationship to difficulty. Over the years, my reasons for training have changed drastically, from physical outcomes to process-oriented or even personality-morphing ones, even though the training itself often looks very similar. I believe this is a natural evolution that comes from recognizing the deeper benefits.

On the OLLIN Program, this is the only required section for our coaches' submissions. They must identify what they are trying to accomplish. Everything else is theory.

The intention is often described as an energy system, such as "I'm training strength or capacity." But this is a slight misconception. The energy system is how we enforce the intention, not the other way around. For example: "I want to feel confident, so I'll use something like strength endurance or mobility to achieve that sensation." Or, "If I wanted to build discipline, I might use a long endurance effort." In a more traditional approach, the intention might be to develop power or explosiveness, in which case I would gear the energy system and the rep/set sequence for that purpose.

This seems intuitive, but I see more people get it wrong than right. When you get it right, you'll start to notice that your intention matches your definition of what it means to be fit.

The Warm-up

I’ve discussed this at length before, so I'll only reiterate that the warm-up is a primer for the main signal. It is the single biggest opportunity to make the most changes in movement patterns. People who warm up poorly, train poorly.

There is no required time period, but it's often thought that the older you are, the more time you need to warm up. I believe this is less a function of "need" and more a function of wisdom. You start to recognize that most of the changes come from detailed observation and adjustment during times when peak output is not the goal.

The warm-up should reflect the patterns and systems that will be seen in the work portion. We start warm-ups generally and aerobically, then move into more specificity and dynamic ranges.

General: Easy, low-impact, aerobically-based movements.

Specific: Primes the energy system focus and movement patterning.

Dynamic: Applies increased force on specific tissue structures and joint combinations that will be seen in the work portion.

It can be hard to tell where the warm-up ends and the work begins because they often take up more than half the session. You can link to my previous article on warming up [here], and an entire page dedicated to some of our favorite warm-up styles [here].

The only rule is that a warm-up cannot overshadow the work. This is based on signaling, not duration (unless duration is the point as with endurance sessions). Signaling is the opening of biological pathways responsible for adaptation. In simple terms: don't warm up with a max back squat just to run 10 miles.

Pre-Fatigue

A pre-fatigue section is most commonly used for strength-endurance outcomes but has also been seen in aerobic capacity sessions. It's used to make the main work portion more difficult or to push past a previously enforced boundary or perception.

This might be one of the more controversial structures we use because when used incorrectly, it can blunt the signaling for top-end expression required for strength and power adaptations.

Many warm-ups for fit people will be pre-fatigue for less-fit individuals, and this is okay because they are generally building a tolerance to volume.

I like a pre-fatigue structure in strength-endurance sessions for smaller musculature like the shoulders before a session that might focus on the chest or back. You can do this by affecting stability or even with post-activation muscle potentiation (overloading). You can also use this in reverse by pre-fatiguing bigger musculature to make the work portion tax smaller, harder-to-target muscles, which is useful for developing greater leg strength since compound movements like the squat tend to keep smaller musculature underdeveloped.

In capacity sessions, you have to be aware that training fatigue resistance is different from training capacity, and getting this wrong will result in a tired athlete, not a fitter one. The "work" portion will need to be at an intensity that can achieve the adaptation, so pre-fatigue work might be used to get the athlete to generate force in a way they are unaccustomed to. I would do this by pre-fatiguing the legs before hard intervals. This requires experimentation as some people have very different reactions to it.

The Work

This is simple: this is why you are here. This part sends the signal to achieve the intention. Whether you're trying to get strong on a particular lift, increase general attributes like endurance and mobility, or tune your conscious state for the day (e.g., increasing creativity or focus), the work portion is used to place the emphasis.

Here, we'll list most—but not all—of the major influences on session design. Certain combinations have predictable sensations, which is a much deeper dive. The goal isn't for me to tell you what to do, but to show you options that you can explore, or that you can start to recognize in our programming.

Reps, sets, loads, and exercises performed outside this portion are largely irrelevant, but here they enforce powerful signals and psychological constraints when they have been constructed properly.

Reps

Strength: 1-25 total reps at above 75% of your 1-rep max (1RM).

Power: 1-25 total reps at above 65% of your 1RM.

Strength Endurance: 25-200 total reps between 40-70% of your 1RM.

Localized Muscular Endurance: 200+ reps (muscularly limited) at less than 50% of your 1RM.

Aerobic Capacity: 200-2000 reps (limited by oxygen). Loading depends on the focus.

Endurance: 2000+ reps (loading is not applicable).

Sets

We break reps into sets to influence how it feels within the system we are trying to affect. Sets are largely defined by the rest between them. Rest allows for increased performance and loading or creates a constraint so the person can increase their tolerance for recovery.

Straight Sets: Straight sets of even reps at the correct percentage will tend to challenge the person because they are required to put forth an equal effort for each set but will feel their performance wane as fatigue sets in. This can give a feeling of hopelessness. We find that straight sets demotivate most athletes and use this structure only when we want strong lessons in perseverance, or when we are using percentages below the proper adaptation threshold and the structure is just a way to go through the movements without "thinking." We do this to set the stage for a conversation or to maintain the habit of showing up, which is not "training" in the traditional sense but can affect the person just as much as a session geared toward pure physiological hardship. It is also the most common way to maintain an ability because it can be used as a reference point.

Ladders:

Ascending: Ascending sets of increasing reps allow warm-ups to be built into the working sets. It gives the sensation that the real work is on the horizon and that the crux will be at the final, pinnacle set. We find this structure very useful for building confidence in the workload. Because of the natural inclination that increasing workload has on reference points to support confidence, we find it a good structure to get people to "buy in" or start hard and deal with the consequences.

Descending: When you start at the peak set of reps, the natural tendency is preservation. It's a way to enforce starting steady and pacing yourself. Much like ascending ladders, descending ladders enforce a behavior but in the opposite manner. They tend to get athletes to "slow down" at the start but finish "fast." This is very useful for competitive athletes who have a hard time regulating their effort. In strength-endurance sessions, they're a great way to emphasize increasing load while decreasing reps for a hypertrophic signal that also leans into strength gains.

Pyramids: A pyramid ladder is both ascending and descending. It is less about starting low or high and more a way to introduce changes in sensations of workload. This could be used to introduce high volume. In strength, we most often use it to increase pull-up strength in low-rep but high-volume output, like a 1-6-1 pyramid. In aerobic training, we use it as a way to require a large volume of work but break it up often to achieve higher average speeds.

Cascades: A cascade is most generally applied to strength-endurance sessions, specifically using supersets or giant sets of focused or complementary work. The requirement is to go to failure or near failure in each set, then immediately switch to the next exercise and repeat this process until the required reps are complete.

Time

For Time: If the goal is time, the outcome is increased intensity at the cost of everything else. Knowing that gaining speed comes at a cost can save you years of learning. "For time" sessions are miniature tests. They are rarely a direct way to improve, but they can show you what you need to improve. They are most often used in concert with aerobic capacity training but can also be used with strength endurance to increase intensity as long as the limitation remains muscular. This can be done by carefully selecting exercises. The duration of the "for time" portion, as well as the pairing of exercises, will largely determine the sensations and the energy system affected. The general barriers happen very quickly:

<5 minutes: This will cause an acute, suffocating effect. It is short enough that most will abandon self-preservation and risk health in order to get through it. Counterintuitively, shorter is more dangerous.

5-10 minutes: This is your average CrossFit session, and is much more dependent on exercise selection to establish the intended sensation. This could be the most transferable time domain for sport, as most "tests" will be in this domain.

15-30 minutes: This time period is sweaty and "feels" like hard work. There will be more muscular fatigue involved, especially when paired with cardiovascular stress. When repeated too frequently, this time period can turn most good programs into "gray" area training, where the person feels as though they are working hard on getting better but are generally just working on getting more fatigued. It is short enough to do frequently, but long enough to cause fatigue.

30-45 minutes: Sessions lasting this long start to fall into a "grind" category. The intensity drops dramatically because rest between sets or implements needs to be considered. In monostructural efforts, the tissues and musculature start to affect the sensations of fatigue.

>60 minutes: Although rare, sessions with a focus on speed for this duration are transformative. It is where the negotiation to slow down or quit will arise many times, especially between minutes 35-45. Other time domains can be trained for specifically, but 60+ minute efforts cannot hide from an underdeveloped aerobic base.

Intervals: Working for specific periods with designated rest times allows for greater acute intensity but also provides an opportunity to train "rest" and recoverability. How they affect you depends on the work-to-rest ratio. The overall time spent working should also be considered to have a desired outcome, not just the work period itself. They are often overutilized in training capacity and underutilized in strength endurance, which has a profound impact on real muscular fatigue when the focus becomes time under tension as opposed to required reps that get done as rapidly as possible. An interval is useful because it clarifies the focus and removes distraction. For this reason, we often use intervals to increase focus. They help in times of precision work, so I have relied on them during editing or technical writing.

AMRAP: "As Many Rounds As Possible" is just another variation of a time-based focus.

EMOM: "Every Minute On The Minute" is a way to describe sequenced required work. It is an inverted principle of an interval that puts the focus on getting the work done to "earn" rest. EMOMs are a great structure for developing consistent pacing and learning how an exercise, movement, or loading affects your ability to accomplish work within a given time, or to recover quickly. It is often used in functional training within capacity-focused sessions, but we have found it very useful to use in strength and power sessions in order to train the phosphogenic pathway responsible for recoverability within top-end lifting.

Accumulation: This pattern usually requires a focus on an increasing amount of work to be done within a given time. It assumes that ultimately, the person will fail or quit, which informs how we might use it in a session to provoke psychological stress and deep introspection. Most often used in capacity sessions, it is also a way to greatly affect strength endurance, especially with grip training, as smaller musculature, when taxed appropriately, needs to be trained to recover quickly.

Work/Rest: The ratio of work to rest will have a great influence on the sensation and adaptation of training.

A 2:1 work-to-rest ratio, like what is used in Tabata intervals, will cause a degradation in output. This is assumed because there is more work than rest. The perception is that this is "harder," but in reality, the effort produces less than favorable physiological results, especially when used too frequently.

A 1:1 ratio is the most common interval. It can be thought of like a straight set in lifting weights and produces similar psychological states. Your performance will degrade, so the number of intervals should be based on this. Unless an intentional mental state is desired, training past performance metrics will only cause more fatigue. This is the most insightful interval structure for recognizing inflection points in effort consistency.

A 1:2 work-to-rest ratio will set the stage for increased output expectations. They are not thought of as easier because the expectation of increased performance comes as a direct result of guaranteed rest.

Exercises

Choosing exercises is first and foremost limited by skill level. Developing skills to perform better, different, or more advanced training concepts can be thought of as a different subject than developing fitness attributes or behaviors. Deepening skill levels allows for exponential expression of fitness attributes, but it does not guarantee it. Developing skills can also be mutually exclusive. There are very skilled and athletic people who are not fit, which means they have a hard time expressing that skill when fatigued.

It should be made clear that developing skills to increase fitness has the unwelcome addition of accommodation. The better we get at an exercise, the more of it we will need to get fitter. OR, we can learn new patterns to which we can apply new stress. Don't be in a hurry to learn new exercises. Although having a greater reference to more skills is better, the foundation for fitness is best learned through foundational movement patterns.

The fundamental patterns are: squat, hinge, push, pull, jump, twist, and bend. The last two are almost always ignored in favor of more complicated, layered, or loaded patterns.

To simplify, think of exercises or patterns as a way to demand energy. The bigger the movement or the more complex, the more energy is required because more joints, tissues, and coordination are needed. The smaller the movement, the more focused the stress. By combining these two concepts, you can shape the sensations of a session when combining the total reps, sets, time domain, and accompanying structure.

Finisher

A finisher is a way to complement your training session. Because we have a rule of needing to complete the session once it is written, a session sometimes gets written with a sense of hesitation, biting off more than we can chew. If we under-program or feel like something needs to be balanced, we use the finisher as a structure to get that work in. The only rule is that it cannot overshadow the work portion.

Cool Down

We do not explicitly write these, but almost every session has an implied cooling period. This time is used to reset the system, to down-regulate the nervous system, and to focus on recovery. It can include some mobility work but is more often than not a time for breathwork and easy aerobic or monostructural work.

The takeaway is that designing a session is complex. The more fitness I explore, the more I find there is to explore. So even if this gives you a starting point to understand why classic sessions feel the way they do, then it is well worth it.

Don't change everything at once. Take one point and explore it. Experiment with reps and sets, or just start noticing what you like about your go-to sessions.

Enjoy.